In Order to Support His Family, Schumann Turned to

César Franck: A Reserved Romantic

University of Houston Moores School of Music

Pupil Project by Hitomi Kato

César Franck'south life spanned most of the important musical events of the nineteenth century. Beethoven died when Franck was merely five years old; as a boy he learned to play Hummel's piano concerto while Hummel was withal alive; he survived Liszt past four years; and he lived to encounter Debussy publish his Cinq Poèmes de Baudelaire and heard Richard Strauss' Tod und Verklärung. Franck'south own influence upon the world can exist seen past his late masterpieces, including the Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue. His entire band of French disciples, known as the Franckists, have too left us with his great influence. Despite all this, Franck was a quiet human being. He did not seek glory; he preferred to live the life of an organist at the church of Sainte-Clotilde. Reserved and hardly recognized during his lifetime, Franck has go one of the chief musicians in the history of western music.

César Franck'south life spanned most of the important musical events of the nineteenth century. Beethoven died when Franck was merely five years old; as a boy he learned to play Hummel's piano concerto while Hummel was withal alive; he survived Liszt past four years; and he lived to encounter Debussy publish his Cinq Poèmes de Baudelaire and heard Richard Strauss' Tod und Verklärung. Franck'south own influence upon the world can exist seen past his late masterpieces, including the Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue. His entire band of French disciples, known as the Franckists, have too left us with his great influence. Despite all this, Franck was a quiet human being. He did not seek glory; he preferred to live the life of an organist at the church of Sainte-Clotilde. Reserved and hardly recognized during his lifetime, Franck has go one of the chief musicians in the history of western music.

Much dispute has occurred over Franck's cultural origins. All the sources agree that he was born in Liège, an bonny provincial city in Kingdom of belgium, on December 10, 1822. Unfortunately, Franck's pupil d'Indy claimed that his teacher had been born "in a land which is peculiarly French, non only in sentiment and linguistic communication, but likewise in its external aspect". 1 Liège officially gained independence from French colonial dominion in 1830, upwards to which bespeak Liège was officially described equally being in the Walloon district of the Netherlands in which the French language was spoken. His mother'due south ancestry was German and his father's people came from the vicinity of Gemmenich, simply a few miles due west of the Aachen border. Eight years afterwards Franck was born, the Flemish and Walloon districts were united under Male monarch Leopold and awarded the condition of an independent country, so at that place tin be no doubt that Franck became Belgian according to this new proclamation. In May 1835 the Franck family unit moved to Paris where his father reapplied for French nationality so that Franck could enroll in the Paris Conservatoire. Afterwards much controversy, he was finally allowed to enter on October 4, 1837. In April 1842 his male parent withdrew him from study and returned to live in Belgium in lodge to concentrate on a career as a virtuoso. And finally, as if this were not enough, the composer himself reapplied for French nationality every bit tardily as 1873 to get a mail as an organist. For these reasons information technology is difficult to say which state should have the benefit of adding Franck's name to its musical heritage due to his cultural origins. 2

At a particularly early age César displayed a talent for music, and hence was destined by his irresponsible and ambitious male parent to follow the profession of a virtuoso. In an age which admired prodigies more then than the previous one (from Mozart and Beethoven to Liszt and Paganini), Nicolas-Joseph Franck was adamant that his elder son earn the fame and fortune he felt his family deserved. Nicolas-Joseph became obsessed with making as much money as possible. When César reached the age of twelve, Nicolas-Joseph, a "petit clerc," did trivial work except to scheme up ways to manage his son's career every bit a virtuoso pianist. He used his administrative position as male parent and maneuvered César into the position of being family provider. 3

In October 1830, Nicholas-Joseph enrolled César at the Liège Conservatory, where he speedily gained first prize for solfege in 1832 and piano in 1834. In 1834, Nicholas-Joseph planned a tour throughout Belgium, including Brussels, where King Leopold heard César play. These concerts produced aught for Nicholas-Joseph, since César was pitted against a variety of well-known artists. On these concerts it was typical for a child prodigy to perform some of his ain compositions, if time immune. César's earliest compositions show no hint of the prediction that he was more than likely to exist a composer than a performer. He produced a couple of sets of variations brilliantes in the accepted way of the day, a "Thou Rondo", some variations on a theme from Hérold's Pré-aux-Clercs, a Concerto classified as Opus 2, two ambitious sounding sonatas for the piano, and besides a number of other fantasias and trios. Of grade it was Nicholas-Joseph who classified his compositions. four

Nicholas-Joseph believed that a bright concert career lay ahead in Paris, so the family moved to the French uppercase. In 1837 César enrolled at the Paris Conservatoire, where he took lessons from Zimmerman for piano, Leborne for composition, and Habeneck for violin. While in Paris he met the Bohemian professor of composition, Antonín Reicha. It is probable that the gentle mysticism Franck afterwards developed in his religious compositions Rédemption and Les Béatitudes was a direct influence from this man. Also, it is from Reicha that Franck learned how to write a proficient fugue. In Reicha, Franck saw the father figure he never saw in Nicholas-Joseph. It was a pity that Reicha died in 1836 shortly after their acquaintance. 5 In 1840, Franck decided to report the organ with Benoist, whom Franck would eventually succeed as Professor of Organ at the Conservatoire.

Leading the life of both a performer and student took its toll on young César. The long struggle to win acclamation as a performer had already begun while Franck was nonetheless a pupil at the Liège Conservatory. Part of his failure came from the blunders his father fabricated in preparing the concerts. Liszt, having heard César on various occasions and "who knew better than anyone what was needed for success in the globe of the salons, lost no time in warning Nicolas-Joseph...that young César seemed deficient in the social qualities required by the career which had been proposed for him. Unfortunately, Liszt's advice was ignored." 6 This statement by Liszt, though probably quite accurate on his function, by no ways should undermine Franck'south playing. He only did not accept the personality for a virtuoso career. Franck himself knew it, and in subsequently years never again appeared on stage as soloist except to perform his own works. Léon Vallas' volume includes part of a letter written by Liszt to Ary Scheffer, the painter:

Liszt was not unaware of certain barriers to success in immature Franck himself. "He will find the route," writes Liszt, "steeper and more rocky than others may, for, every bit I have told you, he fabricated the fundamental error of being christened César-Auguste, and, in addition, I fancy he is defective in that user-friendly social sense that opens all doors before him. For these very reasons, I venture to propose to you that men of spirit and proficient will should rally on his side, and the great friendship which you have for so many years shown towards me makes me hope that you volition forgive whatsoever indiscretion I may have fabricated in thus approaching you at this moment." 7

Nicholas-Joseph, unhappy with César's progress at the Conservatoire, moved the family back to Belgium in April 1842. César did not fifty-fifty have the chance to compete for the Prix de Rome. After an unsuccessful serial of concerts in Belgium the family returned to Paris to try again. Unfortunately, the critics were not altogether kind in their reviews, hinting several times at the high-handedness of the father's exploitation of his son's gifts.

While in Kingdom of belgium Franck experienced a burst of artistic composing activity. Franck's respect for the classical forms was obvious, and in his listen he started to take off from where Beethoven left off. Critics would suggest that he began to

excogitate new possiblilities in a cyclical handling of course...of permitting a recurrence of themes from movement to movement...to economize on material, while avoiding the temptation to make each work a cord of unrelated tunes.

It would be disingenuous to merits that Franck deserves all the credit for this thought. Many commentators have since pointed to Liszt as a musician whose early understanding of the cyclical principle was patently axiomatic. Franck's innovations were wearisome to develop. Even though he may yet have been the first to requite expression to the new philosophy, he can hardly be credited with having used it to create a masterwork. 8 In later works, such equally the Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue, Franck would expand on this thought of cyclical form, in a mode unlike from Liszt, Wagner, and other composers who used the class.

In the early part of 1844, Franck showed signs of declining mental health. In addition to the concert tours prepared past his father, Franck had to teach in order to back up his family. His commitments included the metropolis's boarding schools and a variety of religious institutions, but nigh all of his hard-earned money (which was a pitifully small amount) went to his father's extravagant concert propagandizing for his son. I of these concerts was the disastrous performance of his oratorio Ruth. Franck, unable to handle all the performances and his father'south bullying, somewhen had a modest nervous breakdown and the year 1848 thus marks the culmination of Franck's intentions of leaving his father.

Effectually 1846 Franck became engaged to his educatee, Félicité Saillot (1824 - 1918). She came from a theatrical family and fabricated employ of the theatrical proper noun of her parents, the Desmousseaux, who played at the Comédie-Française. He plant it much more tolerable to spend time with the Desmousseaux family than at his own home. One twenty-four hours Nicholas-Joseph plant a song with the dedication, "To Mlle F. Desmousseaux, in pleasant memories." Nicholas-Joseph tore up the score. He fabricated his son's life unbearable since matrimony would inevitably interfere with his son's future career as a virtuoso pianist, and also interfere with any income coming into the household. Nonetheless, César and Félicité married on February 22, 1848. This year signalled the year of the political revolution of 1848 and of Franck's freedom from his father. 9

After his marriage Franck seems to have been reconciled to the fact that his life would be obscure. He became an organist, a instructor, and a devoted hubby and father. With his engagement as organist of the newly completed basilica of Sainte-Clotilde in early 1858, a new stage of Franck's career began. Beginning at the age of 37, Franck was in command of a magnificent organ, ane of the greatest achievements of the great French organ-architect, Cavaillé-Coll. It was his later-service extemporizations that made Franck famous. People from all over came simply to hear his playing, even though he never caused a kickoff-class pedal-technique despite all his practicing at habitation at his new pedal-lath. This period is when Franck started to publish some works, including the Six Pieces for Organ (1860 - 62). Liszt proclaimed them worthy of a "identify alongside the masterpieces of Johann Sebastian Bach". 10

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 Franck began working on Les Béatitudes, a project which was to occupy his thoughts for a dozen more years. On October 15, 1871, success came unexpectedly with the resurrection of his oratorio Ruth. After having made some important modifications and improvements, the public favorably received the operation. It was during this period that he was laying the foundations for ane of the about remarkable phenomenon of French culture: the cluster of pupils known as the "Franckists". This little grouping of musicians, some of them classical-minded and others advanced Wagnerians, included Henri Duparc, Gabriel Fauré, Camille Saint-Saëns, Théodore Dubois, Ernest Chausson, Vincent d'Indy and many others. According to Edward Burlingame Loma the pupils of Franck,

adhered loyally to their principal's teachings. Since he believed that the classic types of structure, the canon, the fugue, the variation course and the sonata could nevertheless serve every bit a medium for sincere emotion and individual expression, they were bound to imitate his example. Appropriately they unite in emphasizing solidity of structure, based on the classics, every bit the first duty of the artist. If, by the standards of Debussy and other impressionists they are merely reactionaries, these disciples of Franck have remained true to the dictates of their individual artistic consciences, and take never sterilely echoed the past. While this group tin inappreciably exist considered progressive in the mostly accepted pregnant of the word, it has produced much music of a genuinely evolutional grapheme. It is, moreover, representative of one stage of French musical idea. 11

On February one, 1872, Benoist retired from the post of organ professorship at the Conservatoire, an issue that gave Franck the job which firmly established him in the globe of music. He and his disciples were "largely responsible for bringing about at the Conservatoire a new interest in absolute as opposed to dramatic music." 12 Equally a member of the Société Nationale, Franck tried to attend as many meetings as possible (which were not that many since he had to adhere to a rigorous education schedule) in guild to report with care and with indulgence the scores submitted to the Société. The Monday evening meetings, held in Saint-Saëns's house, were a joyous time for Franck, during which they showed each other their latest scores for mutual discussion and criticism.

On November 15, 1874, Franck heard the "Prelude" to Tristan und Isolde, and his memory retained a deep impression of this music. Ane can find hints of it in Franck's works for organ and for orchestra, most of all in Les Éolides, the symphonic poem. The basic thematic ideas in Les Éolides owe profoundly to the chromaticism of Tristan, here to exist observed for the beginning time in Franck's music. Regardless of this Wagnerian influence, the public did not receive the work very well. xiii

In contrast, on January 1880 his Pianoforte Quintet was performed and the audition was taken by surprise at its dramatic intensity. Information technology was a keen success. The musical public and critics alike testified to the agonizing vitality and command of the Quintet. Franck was finally getting some of the credit he long deserved. Ironically, Mrs. César Franck was furious with the work because the dedicatee was Franck's educatee, a female singer with whom the unabridged Conservatoire was in dear.

He was fifty-v before he began the works that were his masterpieces: the Piano Quintet, the Symphonic Variations, the Violin Sonata, the Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue, the String Quartet, and the Symphony in d minor. Although he wrote in many genres (operas, oratorios, cantatas, works for piano, for organ, for orchestra, and chamber music), he is best known for his afterward works, when his genius bloomed in full. Leland Hall described information technology best. He remarks that

all his work bears the stamp of his personality. Like Brahms, he has pronounced idiosyncrasies, among which his fondness for shifting harmonies is the most constantly obvious. The ceaseless alteration of chords, the almost unbroken gliding by half-steps, the lithe sinuousness of all the inner voices seem to wrap his music in a veil, to render it intangible and mystical. Diatonic passages are rare, all is chromatic. Parallel to this is his employ of short phrases, which alone are capable of being treated in this shifting fashion. His melodies are almost invariably dissected, they seldom are built up in broad design. They are resolved into their finest motifs and every bit such are woven and twisted into the close iridescent harmonic cloth with bewildering skill. All is in subtle movement. Yet there is a complete absence of sensuousness, even, for the most function, of dramatic burn down. The overpowering climaxes to which he builds are never a frenzy of emotion; they are superbly at-home and exalted. The structure of his music is strangely inorganic. His material does not develop. He adds phrase upon phrase, item upon detail, with astonishing power to knit and weave closely what comes with what went before. His extraordinary polyphonic skill seems inborn, native to the man. Arthur Coquard said of him that he idea the most complicated things in music quite naturally. Simulated, canon, augmentation, and diminution, the most complex problems of the science of music, he solves without effort....His form...is not organic, but he gives to all his music a unity and compactness by using the same thematic material throughout the movements of a given composition.... Undeniably the sensuous coloring of the Wagnerian school is lacking, though Franck devoted himself almost passionately at one time to the study of Wagner's scores; still, as in the case of Brahms, Franck's scoring, peculiarly his own, is plumbing equipment to the quality of his inspiration.... It is this strange absenteeism of genuinely dramatic and sensuous elements from Franck's music which gives it its quite peculiar stamp, the quality which appeals to usa as a sort of poetry of religion.... His works impress past fineness of detail, not, for all their length and remarkable adherence of structure, by breadth of design. His is intensely an introspective fine art, which weaves well-nigh the simplest subject field and through every measure out most intricate garlands of chromatic harmony. It is a music which is apart from life, spiritual and exalted. Information technology does not reverberate the life of the body, nor that of the sovereign heed, just the life of the spirit. By so reading it we come up to understand his own mental attitude in regard to it, which took no thought of how it impressed the public, merely only of how it matched in performance, in audio, his soul's image of it. xiv

The last pieces Franck wrote were the Three Chorales for organ in 1890. His respect for the classical forms never diminished, and it is this form, the chorale, which Franck adds in his Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue. The 3 Chorales, although the idea may have begun in the Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue, was an attempt at legitimizing his belief in his composing equality to Bach. The tendency toward Bach was finally realized in the Iii Chorales. Franck died in Paris on Saturday, Nov 8, 1890.

The writing of Les Djinns (a symphonic poem with solo piano) and the Piano Quintet seems to have reawakened in Franck his interest in writing for the pianoforte, which he had not done since his younger years. His dearest for the works of Bach led him to use the "prelude and fugue" and then familiar to us from The Well-Tempered Clavier; but he also sought to enlarge the form by linking the two with a chorale. He developed the triptych into a full cyclical form in pure symphonic fashion now known as the Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue.

The Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue was written during the summer of 1884 and was dedicated to Marie Poitevin. In his afterwards pianistic style Franck was influenced by Bach, Beethoven's sonatas, Schumann's Symphonic Etudes, and Liszt'south Weinen Klagen variations. There is a close reminiscence of Wagner's Parsifal in the tune of the chorale. The Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue, "in its basic ideas, besides equally their technical expression for the instrument...wielded a powerful influence over the rising generation of composers in offer them a kind of ideal to follow, a complete expression of the ideals that were opposed fundamentally to the superficial music and so in popular favour." 15

In d'Indy's biography of his instructor he tells us of Franck'due south sudden interest in the piano and how he came to write the Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue:

César Franck, struck by the lack of serious works in this fashion, set to work with a youthful fervour which belied his lx years to try if he could non adapt the old artful forms to the new technique of the piano, a problem which could just be solved by some considerable modifications in the externals of these forms.... Thus it came about that he produced a work which was purely personal, simply in which none of the constructive details were left to chance or improvisation; on the contrary, the materials all serve, without exception, to contribute to the beauty and solidity of the construction. sixteen

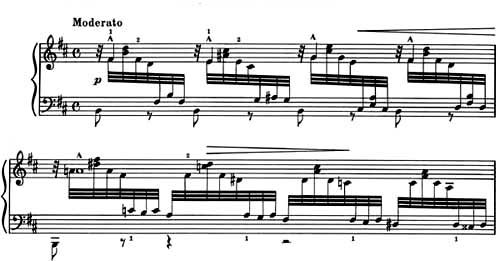

The Prelude begins in the key of B pocket-sized. (Play sound prune.) The main theme is given, surrounded by an arpeggiated accompaniment effigy. Soon a rhapsodic passage, marked a capriccio, hints at the fundamental theme of the entire work. The same two passages appear again, but this time in the dominant minor key of F # . The a capriccio department is lengthened the second time before it leads back to the original key, only after hinting at E b minor. The last section of the Prelude is in B Major. In the transition to the Chorale Franck turns the tonic chord (B Major) into a dominant seventh chord in one measure. Suspending the F # (G b enharmonically spelled) in the tune over into the Chorale, he resolves it merely after playing an Due east b Major chord, the central in which the Chorale starts. E b Major, consequently, is D # Major enharmonically spelled, a third relation from B minor/Major.

The Prelude begins in the key of B pocket-sized. (Play sound prune.) The main theme is given, surrounded by an arpeggiated accompaniment effigy. Soon a rhapsodic passage, marked a capriccio, hints at the fundamental theme of the entire work. The same two passages appear again, but this time in the dominant minor key of F # . The a capriccio department is lengthened the second time before it leads back to the original key, only after hinting at E b minor. The last section of the Prelude is in B Major. In the transition to the Chorale Franck turns the tonic chord (B Major) into a dominant seventh chord in one measure. Suspending the F # (G b enharmonically spelled) in the tune over into the Chorale, he resolves it merely after playing an Due east b Major chord, the central in which the Chorale starts. E b Major, consequently, is D # Major enharmonically spelled, a third relation from B minor/Major.

"The Chorale," says d'Indy,

in three parts, oscillating between E flat minor and C minor, displays two singled-out elements: a superb and expressive phrase which foreshadows and prepares the way for the subject field of the Fugue, and the Chorale proper, of which the three prophetic words -- if we may so call them -- coil forth in sonorous volutions, in a serene, religious majesty. 17

The kickoff section (Play audio clip.) presents a "phrase" suggestive of the bailiwick of the Fugue. This start section modulates to C minor. The start "discussion" of the Chorale, according to d'Indy, starts at measure 68 with the rolling of the organ-like chords. (Play sound clip.) The next section presents the "phrase" again, this time modulating to the subdominant, F minor. The 2nd "give-and-take" is so proclaimed in F minor. The last section suggests a slight variation of the "phrase" past using sequences: there is a climax, preparing the final "word," in the tonic key of the Chorale, E b small.

The kickoff section (Play audio clip.) presents a "phrase" suggestive of the bailiwick of the Fugue. This start section modulates to C minor. The start "discussion" of the Chorale, according to d'Indy, starts at measure 68 with the rolling of the organ-like chords. (Play sound clip.) The next section presents the "phrase" again, this time modulating to the subdominant, F minor. The 2nd "give-and-take" is so proclaimed in F minor. The last section suggests a slight variation of the "phrase" past using sequences: there is a climax, preparing the final "word," in the tonic key of the Chorale, E b small.

Afterwards an interlude which takes us from E b pocket-size to B minor (the original central) the Fugue takes off. (Play audio clip.) Franck uses the contrapuntal technique of inverting the discipline in the center of the fugue. (Play audio prune.) After the evolution of the Fugue the Prelude returns one time more than, with a rhythmic vigor which is used to back-trail a restatement of the theme of the Chorale, and so the field of study of the Fugue itself enters in the tonic. All three chief elements of the piece of work are combined at the end and "enfolds us in its triumphant personality until the final peal which brings the piece of work to a shut" 18 in B Major.

Afterwards an interlude which takes us from E b pocket-size to B minor (the original central) the Fugue takes off. (Play audio clip.) Franck uses the contrapuntal technique of inverting the discipline in the center of the fugue. (Play audio prune.) After the evolution of the Fugue the Prelude returns one time more than, with a rhythmic vigor which is used to back-trail a restatement of the theme of the Chorale, and so the field of study of the Fugue itself enters in the tonic. All three chief elements of the piece of work are combined at the end and "enfolds us in its triumphant personality until the final peal which brings the piece of work to a shut" 18 in B Major.

As can exist seen past this brief analysis, Franck was extremely fond of radical modulations, and encouraged his students to practice and so in their compositions. The form of this piece shows Franck'due south early obsession with the cyclic course, peculiarly apparent in the last section after the Fugue, when all the themes restate themselves. His rich chromatic bass tin can be heard throughout the piece, indicative of the influence the organ pedals had on him. Because Franck came up with the "prelude, chorale, and fugue", information technology is a genre in itself, simply equally noted earlier, indebted to Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier and other pieces like information technology.

A quiet and reserved human being, César Franck, though inappreciably recognized in his lifetime, left us with a bully legacy: his late mature music, which was his outlet from a lifetime of resignation. He left us non only with his music, but also left us with a new generation of wonderful French composers. Without his influence on the younger generation the world could quite perchance never have known a Debussy (much every bit he hated to acknowledge it) or a Fauré. But permit me exit it up to Franck to say a little about himself: "I, too, have written some beautiful things." 19

1 Vincent d'Indy, César Franck, trans. Rosa Newmarch (London: John Lane, 1910), 29.

two Stanley Sadie, ed., The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (London, Macmillan Publishers Express, 1980).

three Laurence Davies, César Franck and His Circle (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1970), 42.

4 Ibid., 46 - 47.

5 Laurence Davies, Franck (London: J.1000. Dent and Sons Ltd., 1973), vi.

six Idem, César Franck and His Circle, 43.

seven Léon Vallas, César Franck, trans. Hubert Foss (New York: Oxford University Printing, 1951), 74 - 75.

8 Idem, César Franck and His Circumvolve, 53 - 54.

9 Léon Vallas, César Franck, 81 - 93.

10 Ibid., 127.

11 Edward Burlingame Hill, Modern French Music (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Visitor, 1924), 112 - 113.

12 David Ewen, The World of Great Composers (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1962), 270.

13 Léon Vallas, César Franck, 153 - 156.

fourteen Ibid., 275 - 279.

xv Ibid., 184 - 185.

16 Vincent d'Indy, César Franck, 163 - 164.

17 Ibid., 164.

xviii Ibid., 168.

19 David Ewen, The Earth of Great Composers, 280.

Source: https://uh.edu/~tkoozin/projects/hitomi/Franck.html

0 Response to "In Order to Support His Family, Schumann Turned to"

Post a Comment